Sarah Ida Fowler Morgan penned this diary of a southern belle that tells of her ‘ideal beau.’ She was born in New Orleans on February 28, 1842 and was the seventh child of Judge Thomas Morgan and his second wife, Sarah Hunt Fowler. In 1850, the family relocated to Baton Rouge, where Judge Morgan worked as a district judge. Life as she knew it changed at the beginning of the Civil War.

Civil War Diary (From March 1862 until April 1865)

In April 1861, her brother Henry Morgan, died in a duel and later the same year her father Judge Morgan died. When Dawson began her diary in January 1862, she was still mourning the loss of her brother and father. In Baton Rouge with her mother and sisters, Sarah recorded the scarcity of food and household items because of the Union blockade.

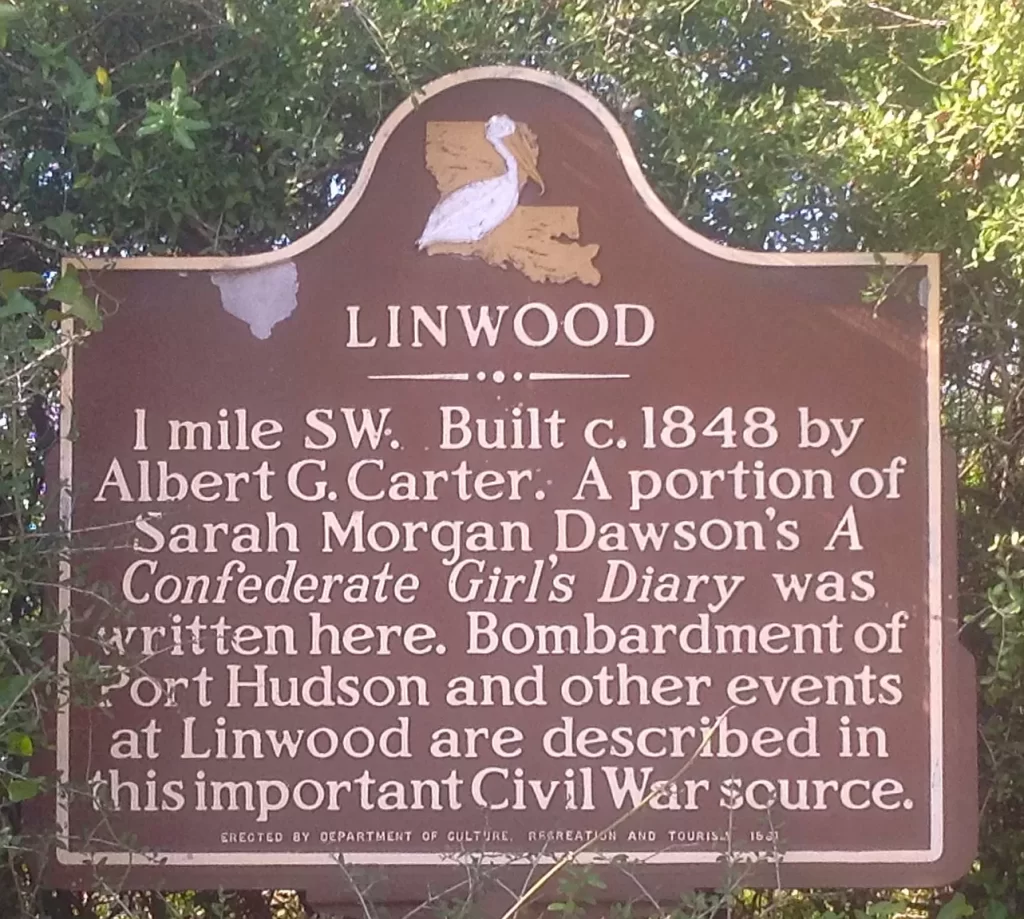

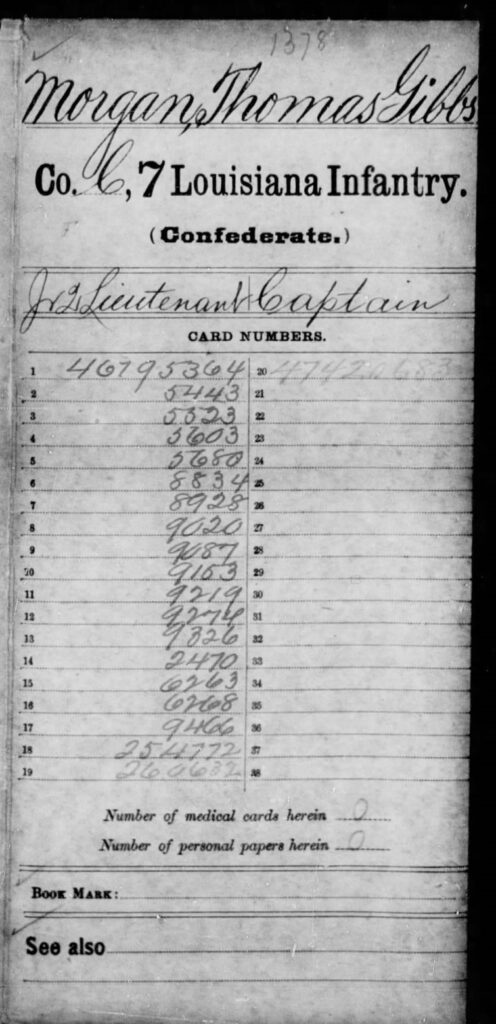

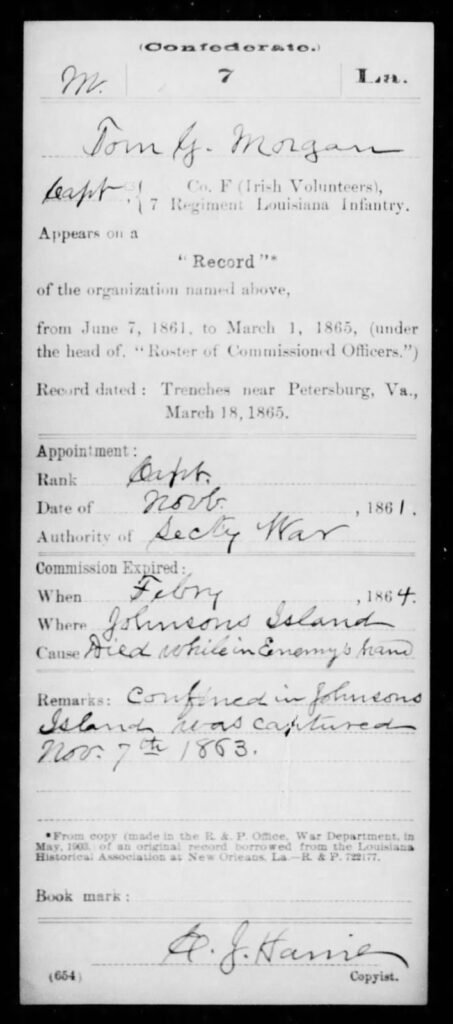

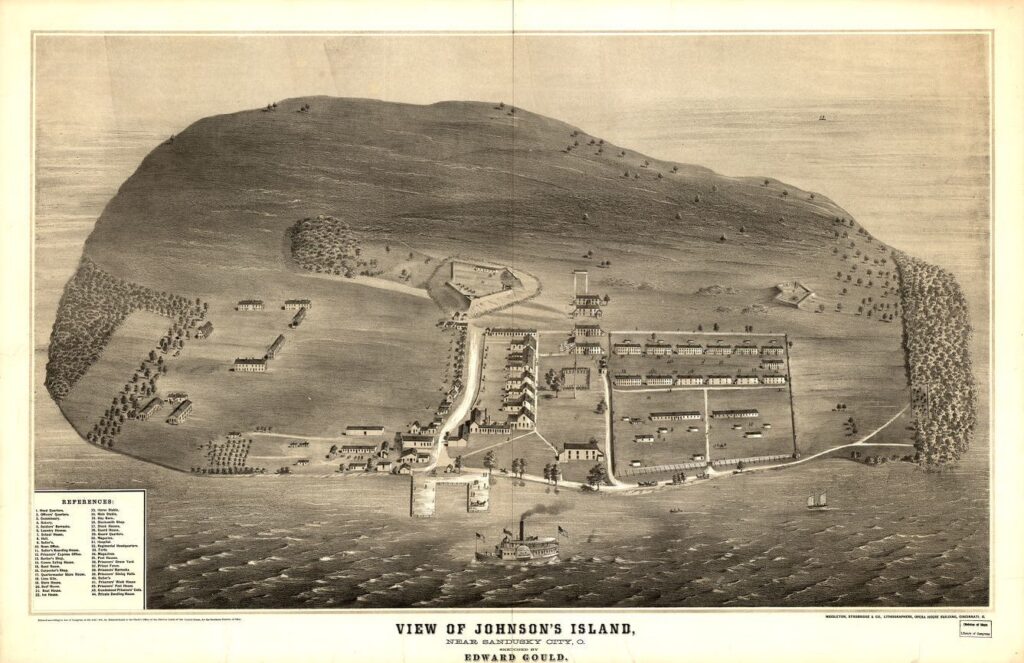

In April 1862, New Orleans was captured by the Union and by May of that year, Baton Rouge was under assault in August. In August 1862 the Union army sacked their Baton Rouge home, and the threat of further violence forced them to abandon it. Fleeing Baton Rouge, they began living at her brother Thomas’s wife’s family plantation in August 1862. The “Linwood” Carter plantation, located 30 miles north of Baton Rouge in East Feliciana Parish, is where she wrote about her isolation from the hardships of the war as well as the frequent visits by groups of Confederate soldiers nearby. (Her brother Thomas Gibbes Morgan fought under Stonewall Jackson and had been badly wounded at Antietam. He recovered only to be taken prisoner on November 7, 1863, to Johnston’s Island in Ohio and died of tonsilitis January 21, 1864.)

Click to enlarge photographs

Life after the Civil War

In 1872, Sarah, her mother, and sisters moved to Columbia, South Carolina. Sarah began writing editorials for the Charleston News & Courier under the pen name “Mr. Fowler.” She was a staunch supporter of women’s equality, she often expressed her feminist views in both her editorials and her diary. Sarah Morgan worked throughout 1873 until she married the newspaper’s editor Francis Warrington Dawson. They had three children. Her husband Francis Dawson was outspoken against violence, but one day he confronted Dr. Thomas B. McDow of making “dishonorable advances” toward the Swiss governess of his children. The physician shot and killed him. McDow was acquitted, however, claiming self-defense.

After her husband’s murder in 1889, Sarah Morgan Dawson moved to Paris to live with her son Warrington Dawson, where she published a French version of the Brer Rabbit stories in 1903. She died in Paris on May 5, 1909.

A Confederate Girl’s Diary by Sarah Fowler Morgan Dawson faithfully recorded her thoughts and experiences of the war. Her early entries, which deal primarily with Baton Rouge society, give way to detailed accounts of her family’s daily fears about living in Baton Rouge as the fighting encroaches upon the city. Several times Dawson describes her family chaotically fleeing their home on foot, bringing only what they could carry with them. She also includes accounts of slaves faithfully rescuing their masters’ children and household goods without the opportunity to salvage anything of their own. Although a strong supporter of the Confederacy, Dawson does not hesitate to record the kindness among members of the Federal guard, her disapproval of women’s secessionist banter, and her despair over the South’s future. The Diary ‘s final pages are filled with tragedy as Dawson recounts the anguish of losing her two brothers, the fall of the Confederacy, and the shooting of Abraham Lincoln. ~ Summary From Documenting the American South [1]

6 May 1862 Pages 81-85

Shall I say here, if not aloud, why it is I have never yet fallen in love? Simply because I have yet to meet the man I would be willing to acknowledge as my lord and master. For unconfessed to myself, until very recently, I have dressed up an image in my heart, and have unconsciously worshipped it under the name of Beau Ideal. Not a very impossible one, for doubtless there are many such, though the genus is not to be· found in Baton Rouge; but still I am ashamed to acknowledge such a schoolgirl weakness, even to myself; for I know if any moon-struck girl described her beau ideal to me, the only sympathy she would get would be a slight elevation of the nose. I hate sentimentality; but way down in my heart, I am afraid I rather like sentiment.

Do you remember the distinction? Well, my lord and master must be some one I shall never have to blush for, or be ashamed to acknowledge; the one that, after God, I shall most venerate and respect; and as I cannot respect a fool, he must be intelligent. I place that first, for I consider it the chief qualification in man, just as I believe a pure heart is the chief beauty of a woman. Yes, and he must be smart enough for two; his brains must do duty for both, and supply all my deficiencies.” Now that is settled, I hardly know what comes next; I place all other qualifications on a single level. Oh! I forgot amiability! That ranks immediately after intelligence; sometimes I am inclined to give it the precedence, for I am satisfied that no home is a happy one where it is not an inmate. He must be amiable enough to set me a good example, and philosophical enough to teach me to laugh at the petty annoyance of this life. I could be forever cheerful where I had a kind smile to meet mine; loving hearts and kind words are as necessary as the air I breath[e], so my Master must be amiable. He must be brave as man can be; brave to madness, even. I would hate him if I saw him flinch for an instant while standing at the mouth of a loaded cannon.

Let him die, if necessary; but as to a coward-! Merci! je n’en veux pas! [2] I am no coward; it does not run in our blood; so how could I respect a man who was one? O what unspeakable contempt I would feel for him!

He must be a man of the world. I have mixed so little in society, have so great a distaste for it, and so much mauvaise honte, [3] that I am by no means calculated to shine there; but I would wish him to do so. Of course he must be entitled to it by birth and education; I could marry no other than a gentleman. I do not mean gentleman in the vulgar sense-handsome young fellow with well oiled hair, and even more impudence than pomatum; such a beauty, and so rich! (although he may have been a shoe black when very young)-, no; I mean gentleman in my signification of the term, which, to the qualities mentioned a while ago, adds principle as firm and immoveable-as the rock of Gibralta [sic], a sense of honor as nice and delicate as a woman’s, and a noble, generous, pure heart. That is what I call a gentleman; how many of my present friends. answer to the description? There are many such in this world, though.

He may be as ugly as mud, and I will never think of it; the more ugly he is, the more intelligent he will be. Who ever saw a perfect face on man ‘or woman that showed a spark of intelect [sic]? Theil, the uglier he is, the better he will be; your handsome men care much more for their beauty than they do for their-morals, I never saw a blackleg [4] that I know of, but from what I have heard, am inclined to believe they are all good looking.

I would not wish him to-be rich; “poor and content is rich enough.” [5] I would like him to be just what I have been all my life, neither rich nor poor. I am satisfied that is the true secret of happiness. As I said before, he must be au-fait in the ways of the world. There is a name-less something in the air, or manner of a perfect gentleman which has a perfect fascination for me, though I cannot give it a: name. I always look for it though, and feel as though something was missing when l do not find it, which means ninety nine cases out of every hundred. Above all, he must have-a Profession! If he is rich, smash! go the Banks some fine morning, and Master is turned adrift on the tender mercies of the world, without the means to turn an honest penny, even if he had the inclination or energy, which most rich men do not. “He cannot work, to beg he is ashamed,” [6] so he quietly settles down, and goes to the dogs, hot forgetting you, but insisting on your company for the first-time in your married life. If he is poor, the Banks may fail without hurting him; his profession gives him a position until he can claim and, sustain it by his own exertions; success crowns his efforts at last: Poverty, with such a person as I have described, is infinitely better than wealth in abundance, with a fool of a parvenue. I am satisfied that it is the life for me.

Woe he to me, if I could feel superior to him for an instant! Black misery would drape the rest of my young days, and settled despair grace my old ones. I need some one I would delight to acknowledge as the model of all goodness and intelect on earth; someone to look up to, and admire unfeignedly, some one to lead me upward. and teach me to be worthy of his regard. From what I have said, one of these days, looking back when I am an old maid, I will turn up my nose and say “Why did you not say marry a teacher at once? better marry a man and engage a teacher afterwards.” Merci, my oId maid! let me have my talk out while I am young! In a dozen years from now, perhaps it will be only reasonable for me to turn up my nose at all such folly, fancy sketches, etc. Mais en attendant [7] let me have my fun out, will you?

I have described such a man as I firmly believe exists, such a one as I believe I should marry, if I expect to be happy. One that I could respect above all others; one, whose children (I may here say I have the greatest penchant for widowers and lawyers) I could bring up in the belief my mother taught hers, that their father was the greatest and best man in the world. When I meet such a man, then, O Gibbes! I will tumble heels over head in love, and get married forthwith, even if I had to do the courting! Until then, Cupid spare my heart! I will need it all for him, and am inclined to believe that hearts and eggs are much the same: they keep fresh enough if you let them alone, but get wofully addled by being tossed about. Cupid spare my heart, I say! I prefer an omlette of fresh eggs, and perhaps he does too! “Go thy way; when I have a more convenient season, I will send for thee!” [8]

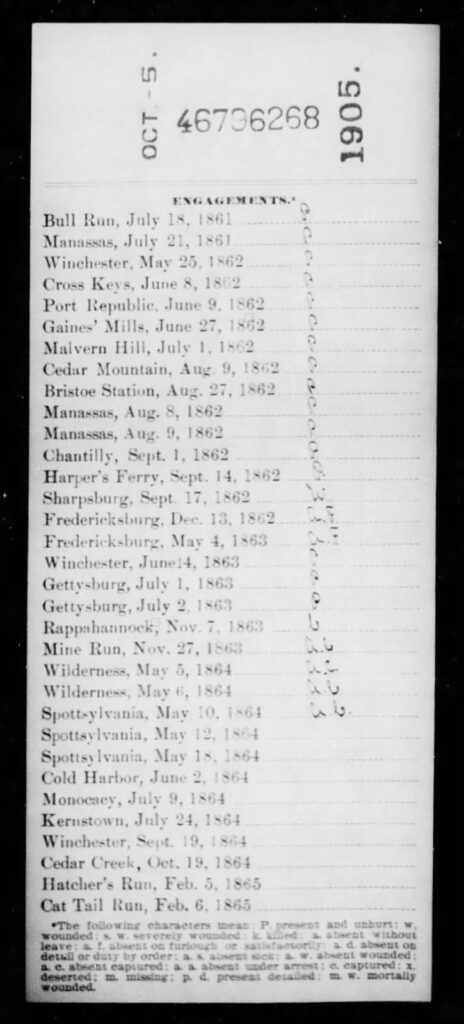

Below are Thomas Gibbes Morgan, Jr. military records for the Civil War showing his service in the confederacy and that he died in the Confederate officer prisoner camp Johnston’s Island located on Lake Erie in Ohio. (click on image to enlarge)

Source: Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Louisiana, Carded Records Showing Military Service of Soldiers Who Fought in Confederate Organizations, compiled 1903 - 1927, Publication number M320, Record Group 109. Louisiana, Roll: 0181.

[[1] https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/dawson/dawson.html

[2] Translation: Thanks! I don’t want any of it!

[3] Self-consciousness

[4] Professional gambler or sharper (thief or con-man; many were portrayed as romantic figures in the 18th century.

[5] Shakespeare, Othello

[6] Luke 16:5

[7] But in the meantime

[8] Acts 24:25

[9] Gould, Edward. View of Johnson’s Island, near Sandusky City, Ohio. Cincinnati, Ohio, Middleton, Strobridge & Co., Lithographers, 1865. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/99447489/.